Reviewing particle shape descriptors

Particle shape is known to affect the macro properties of granular materials. For instance, angular sands tend to possess a higher void ratio, a larger compressibility potential, a higher friction angle, greater anisotropy and non-coaxially [1], and higher hydraulic conductivity [2] than the rounded counterpart. However, limited research has attempted to quantify these effects with appropriate true particle shape descriptors. Elongation, roundness and roughness are three important aspects in particle shape [3]. Some approaches that can be used to characterise the particle shape from different aspects are summarised in Table 1.

Despite a large number of 2D shape parameters that have been developed, as shown in Table 1, they may be inaccurate because of the random projection, especially for platy grains such as mica shown in Figure 1. 3D shape parameters [4, 5] are available, but the number is limited. Furthermore, academics attempted to unify the shape parameters. Specifically, Wadell [6] adopted the ratio of roundness and sphericity to express the image of a solid. CHO, Dodds and Santamarina [3] developed regularity, which is the average of sphericity and roundness. A total shape index was also introduced by Parylak [7], which considers sphericity, angularity and roughness; further details can also be found in the work of Ziȩba [8]. However, the same shape parameter may be calculated using different equations.

Table 1 Overview of shape descriptors

| Scale | Shape descriptors | Definition | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| — | Sphericity [6] | The ratio of sphere surface that has the same volume as the particle to the real surface of the particle.MinR/MaxR in Particles8_Plus. MinR and MaxR are the radius of the inscribed and enclosing circles at the centre of mass, respectively. | The proximity of a particle to a sphere;Can be an ambiguous indicator unless coupling with 'shape factor' [9] because disc-like bodies may have the same sphericity as rod-like or bladed bodies.Different definitions in computer programs; |

| Sphericity (Elongation) | Circularity | (4*π*Area)/(Perimeter2) | 2D sphericity |

| — | Aspect Ratio | Feret/ Breadth | Feret = Major axis;Breadth = Minor axis |

| — | ModRatio | (2*MinR)/ Feret | MinR: Radius of the inscribed circle centred at the centre of mass, |

| Roundness (Angularity) | Roundness [6] | The ratio of average curvature at particle corner to overall particle curvature;4*Area/(π*Feret2) in Particles8_Plus, where Feret is the Major axis. | The extent to which the corners and edges have been rounded;Not always appropriate to quantify the finer detail of particle contour, for crushed particles in particular [10].Different definitions in computer programs;Imply angularity and texture;Together with sphericity are easy to use with a 2D chart (Figure 2.3). |

| — | Compactness | (SQRT[(4*Area)/ π])/ Feret | |

| — | Solidity | Area/ConvexArea | ConvexArea: Area of the Convex Hull polygon. |

| — | Convexity | ConvexHull/Perimeter | |

| — | RFactor | ConvexHull/( Feret*π) | |

| — | Fourier series[11] | Shape (wave of the profile) is obtained by measuring the relationship between radii and the angle between the measurements using Fourier series. | |

| Smoothness (Roughness) | Fourier descriptors [12] | Calculation from the Fourier series coefficients. | Independents of the size of grain and the relative position in the input image;Lower frequency descriptors indicate the integral particle shape while the higher frequency descriptors relate to textural qualities [13] |

| — | Fractal dimension [14] | Describe the capability of a rough boundary approaching the particle. Fractal dimension (D) is derived from the relation between the approximate profile length L, the number of segments N and the segment length r. | Characterises shape which cannot be described by other traditional Euclidean geometry;Highly depends on the segment lengths. |

Figure 1. 2D particle shape is subject to the projection, especially for platy grains such as mica [15].

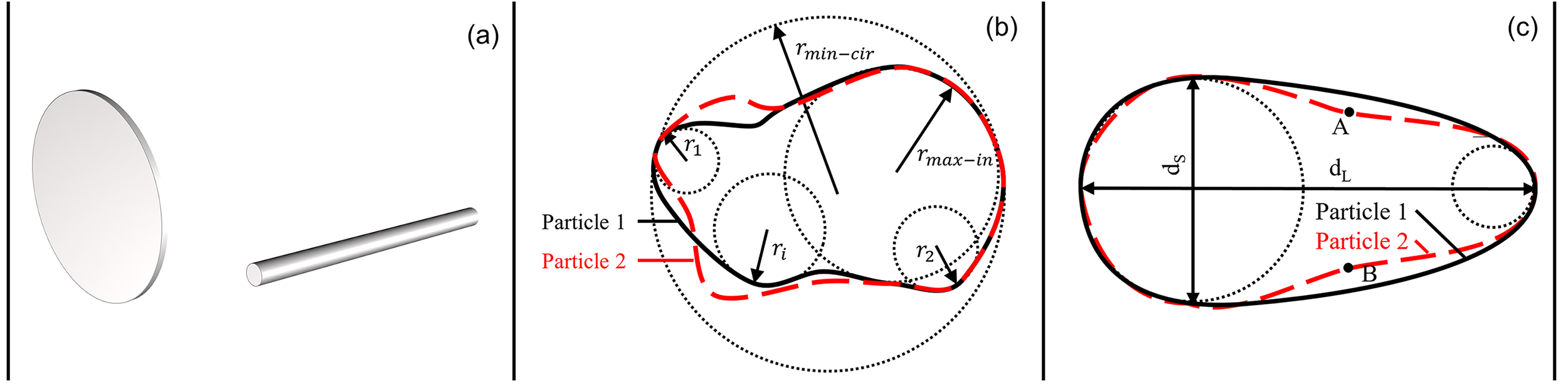

Critically selecting three-dimensional sphericity and roundness

A number of definitions (and corresponding equations) have been proposed in the literature to calculate three-dimensional (3D) sphericity and roundness. Table 2 summarises some of these definitions and formulae to compute 3D sphericity (S1 – S5) employing different parameters. While particle volume V and surface area SA are used in S1 and S2, the radius of maximum inscribed and minimum circum-scribed sphere (rmax-in and rmin-cir, respectively) are adopted in S3. The length of principal axes of the particle di is employed in S4 and S5. However, none of these descriptors can distinguish all particles with different shapes. For example, S1 and S2 cannot distinguish between disc-shape particles and rod-shape particles because they may have the same surface area and volume, as depicted in Fig. 2(a). In Fig. 2(b) and Fig. 2(c) S3 cannot recognise the difference between particle 1 and particle 2 because they have the same maximum inscribed circle and the minimum circum-scribed circle. Moreover, S4 and S5 cannot distinguish particle 1 and particle 2 in Fig. 2(c) since they have the same principle axes if considering the two particles have the same thickness in 3D.

Table 2 A summary of various definitions of sphericity

| Notation | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | The ratio of the surface area of the equivalent sphere of a particle to the real surface area of the particle. V is particle volume and SA is particle surface area. | [6] |

| S2 | The cubic order of S1. | [16] |

| S3 | The ratio of the radius of the maximum inscribed circle (sphere in 3D) to the radius () of the minimum circum-scribed circle of a particle shown in Fig. 2(b). | [17] |

| S4 | The ratio of the maximum axial length (dS) to the minimum axial length (dL) of a particle. | [18] |

| S5 | Fitting a particle to an ellipsoid, dS, dI and dL are the shortest, intermediate and the longest axial length of the fitted ellipsoid. | [19] |

Figure 2. Examples of potential shortcomings of the various definitions of sphericity and roundness: (a) Example of two particles of different shape but same sphericity (S1 and S2 in Table 1); (b) Example of two particles of different shape but same sphericity (S3 in Table 1) and roundness. (c) Example of two particles of different shape but same sphericity (S4 and S5 in Table 1) and roundness.

Please cite our papers related to characterise particle shape from CT images

- Fei W, Narsilio GA, Disfani MM. Impact of three-dimensional sphericity and roundness on heat transfer in granular materials. Powder Technology 2019, 355:770-781, doi.

- Fei W, Narsilio GA. Impact of Three-Dimensional Sphericity and Roundness on Coordination Number. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2020, 146:06020025, doi.

- Fei W, Narsilio GA. Network analysis of heat transfer in sands. Computers and Geotechnics 2020, 127:103773, doi.

- Fei W, Narsilio GA, van der Linden JH, Disfani MM. Quantifying the impact of rigid interparticle structures on heat transfer in granular materials using networks. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2019, 143:118514, doi.

Reference

[1] Y. Yang, W. Fei, H.-S. Yu, J. Ooi, M. Rotter, Experimental study of anisotropy and non-coaxiality of granular solids, Granular Matter, 17 (2015) 189-196.

[2] A.F. Cabalar, N. Akbulut, Evaluation of actual and estimated hydraulic conductivity of sands with different gradation and shape, SpringerPlus, 5 (2016) 820.

[3] G. CHO, J. Dodds, J. Santamarina, Particle Shape Effects on Packing Density, Stiffness and Strength of Natural and Crushed Sands-Internal Report, Georgia Institute of Technology, 33pp, (2004).

[4] M.A. Taylor, Quantitative measures for shape and size of particles, Powder Technology, 124 (2002) 94-100.

[5] B. Zhou, J. Wang, H. Wang, Three-dimensional sphericity, roundness and fractal dimension of sand particles, Géotechnique, (2017) 1-13.

[6] H. Wadell, Volume, shape, and roundness of rock particles, The Journal of Geology, 40 (1932) 443-451.

[7] K. Parylak, Charakterystyka kształtu cząstek drobnoziarnistych gruntów niespoistych i jej znaczenie w ocenie wytrzymałości, Zeszyty Naukowe. Budownictwo/Politechnika Śląska, (2000) 3-130.

[8] Z. Ziȩba, Influence of soil particle shape on saturated hydraulic conductivity, J. Hydrol. Hydromech., 65 (2017) 80-87.

[9] T. Zingg, Beitrag zur schotteranalyse, 1935.

[10] G. Lees, A new method for determining the angularity of particles, Sedimentology, 3 (1964) 2-21.

[11] R. Ehrlich, B. Weinberg, An exact method for characterization of grain shape, Journal of sedimentary research, 40 (1970).

[12] D.W. Luerkens, Theory and application of morphological analysis: fine particles and surfaces, CRC press1991.

[13] I. Kunttu, L. Lepisto, J. Rauhamaa, A. Visa, Multiscale Fourier descriptor for shape classification, Image Analysis and Processing, 2003. Proceedings. 12th International Conference on, IEEE, 2003, pp. 536-541.

[14] B. Mandelbrot, Les objects fractals: forme, hazard et dimension, Flammarion, Paris, 1975.

[15] TEACHERS, Mica, 2012.

[16] D. Legland, I. Arganda-Carreras, P. Andrey, MorphoLibJ: integrated library and plugins for mathematical morphology with ImageJ, Bioinformatics, 32 (2016) 3532-3534.

[17] G. Cho, J. Dodds, J. Santamarina, Particle Shape Effects on Packing Density, Stiffness and Strength of Natural and Crushed Sands-Internal Report, Georgia Institute of Technology, 33pp, (2006).

[18] R.D. Hryciw, J. Zheng, K. Shetler, Particle roundness and sphericity from images of assemblies by chart estimates and computer methods, Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 142 (2016) 04016038.

[19] E.D. Sneed, R.L. Folk, Pebbles in the lower Colorado River, Texas a study in particle morphogenesis, The Journal of Geology, 66 (1958) 114-150.