Why is microstructure important to heat transfer?

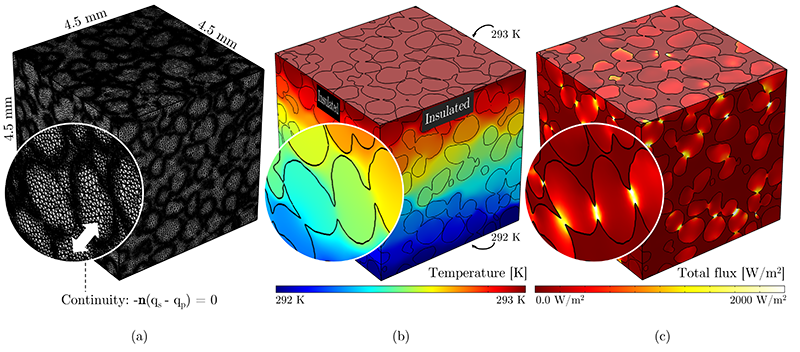

Heat transfer is one of the dominant processes in energy systems studied in geothermal engineering [1], pebble bed reactor [2] and thermal energy storage [3] comprising granular materials, to name a few examples. The effective thermal conductivity (λeff) is a critical variable used to describe how easily heat travels within (granular) materials. Therefore, a thorough understanding of heat transfer processes and predicting λeff accurately and efficiently is of great importance.

The λeff characterises heat transfer of a granular material at macroscale similar to what porosity does when characterising the number of voids within the granular assembly. Hence, λeff models based on porosity alone miss the information of the particle geometry at the microscale and particle arrangement at mesoscale. Bypassing these microstructural parameters may be the cause of the differences between the λeff from models and experimental measurements [4-6]. The lack of microstructural characterisations for granular materials is due to the limited access to the microstructure, especially for natural sands comprising particles with irregular shapes. Even though some λeff models [7-9] attempted to involve the effect of particle/pore shape, the shape was described by aspect ratio which only works well for regular particles such as spheres and ellipsoids [10]. With the advent of X-ray computed tomography (CT), it is possible to generate sequential cross-sectional images of soil and rock samples. The sequential images include the interior structural information in the samples and can be stacked together to digitally reconstruct the sample microstructure in three-dimensions (3D). Based on the digital sample, it is feasible to extract geometrical parameters such as particle shape descriptors using image post-processing algorithms. Although a number of parameters [11-16] have been attempted in quantifying particle shape, most of them are two-dimensional and even different equations were employed to calculate the same parameter. For instance, the sphericity in [12] and [11] depends on particle surface area and volume, while the sphericity in [17] is computed using the radii of the maximum-inscribed sphere and minimum circumscribed sphere. Some other studies [14, 15] considers aspect ratio identical to sphericity, and its value is related to different combinations of axial length. Consequently, the selection of particle shape descriptors and their defining equations should be compared and selected carefully. In gas/fluid stagnant granular materials, the heat transfer paths can be classified into (1) particle conduction; (2) interparticle conduction; (3) particle-gas/fluid-particle conduction and (4) heat radiation from solid surface to other media. The last three heat transfer mechanisms indicate the importance of structural arrangement to λeff prediction. The coordination number (CN) describes the connection of a target particle with its surrounding particles and is well related to mechanical stability [18]. However, for granular materials under loads, the average coordination number (CNave) cannot fully characterise the spatial change of the microstructure, and the variation of interparticle contact area which is vital to heat transfer [6, 19]. According to rigidity theory, interparticle triangle structures can resist more deformation compared with the quadrilateral structure. Nevertheless, their impact on λeff has not been studied yet.

Characteristics about particle connectivity (except for CN) are still scarce. An order characteristic [20] or Voronoi tessellation [21] can measure the particle connectivity but for sphere packings rather than natural sands. Complex network theory has gained significant success in presenting social networks [22] and infrastructure systems [23]. By presenting a granular material as a network consisting of nodes and edges, complex network theory has also been applied to granular materials to study the impact of microstructure on mechanical behaviour [24] and fluid flow [25]. The physical meanings of nodes and edges vary according to the application. Contact networks are usually used to investigate the mechanical behaviour of granular materials by presenting a particle as a node and an interparticle contact as an edge. Network features from the contact network also have the ability to detect the shear band in an early stage [26]. The aforementioned interparticle triangle structure corresponds to the concept of 3-cycle in complex network theory. However, complex network theory has not been introduced to investigate the impact of microstructure on heat transfer. It is also noticeable that heat transfer through gaps (near-contact) between adjacent particles cannot be quantified by features from the contact network which only considers the interparticle contacts. Only a few pioneering simulation tools called thermal network models involved near-contacts, but they focus on λeff calculation [1, 27] rather than extracting mesoscale parameters.

Even though granular materials are complex systems and the complex network-based approach offers an opportunity to enrich particle connectivity features (e.g., degree, centrality measures, cycles and clustering coefficients) [28], considering many of them together with traditional parameters such as particle size and porosity may increase the redundancy of λeff models. Hence, the most important network features related to λeff are required to be screened to quantify the particle arrangement succinctly at multiple scales. The screening processes are implemented objectively using machine learning (ML) techniques in my PhD project (i.e., feature selection). In addition to the feature selection, ML also shows great potential for predicting material properties in a more efficient, objective and autonomous process [29]. λeff prediction using ML methods have been studied in [27, 30, 31]. However, particle connectivity parameters were absent and the studies used artificial materials.

References

[1] T.S. Yun, T.M. Evans, Three-dimensional random network model for thermal conductivity in particulate materials, Computers and Geotechnics, 37 (2010) 991-998.

[2] M. Moscardini, Y. Gan, S. Pupeschi, M. Kamlah, Discrete element method for effective thermal conductivity of packed pebbles accounting for the Smoluchowski effect, Fusion Engineering and Design, 127 (2018) 192-201.

[3] W.J. Cole, K.M. Powell, T.F. Edgar, Optimization and advanced control of thermal energy storage systems, Reviews in Chemical Engineering, 28 (2012) 81-99.

[4] W. Van Antwerpen, C. Du Toit, P. Rousseau, A review of correlations to model the packing structure and effective thermal conductivity in packed beds of mono-sized spherical particles, Nuclear Engineering and design, 240 (2010) 1803-1818.

[5] Z. Abdulagatova, I. Abdulagatov, V. Emirov, Effect of temperature and pressure on the thermal conductivity of sandstone, International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 46 (2009) 1055-1071.

[6] A.M. Abyzov, A.V. Goryunov, F.M. Shakhov, Effective thermal conductivity of disperse materials. I. Compliance of common models with experimental data, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 67 (2013) 752-767.

[7] P. Zehner, E.U. Schlunder, Thermal Conductivity of Granular Materials at Moderate Temperatures, Chemie. Ingr-Tech., 42 (1970) 933-941.

[8] H. Fricke, A mathematical treatment of the electric conductivity and capacity of disperse systems I. The electric conductivity of a suspension of homogeneous spheroids, Physical Review, 24 (1924) 575.

[9] T. Keller, U. Motschmann, L. Engelhard, Modelling the poroelasticity of rocks and ice, Geophysical prospecting, 47 (2001) 509-526.

[10] W. Fei, G.A. Narsilio, M.M. Disfani, Impact of three-dimensional sphericity and roundness on heat transfer in granular materials, Powder Technology, 355 (2019) 770-781.

[11] H. Wadell, Volume, shape, and roundness of rock particles, The Journal of Geology, 40 (1932) 443-451.

[12] D. Legland, I. Arganda-Carreras, P. Andrey, MorphoLibJ: integrated library and plugins for mathematical morphology with ImageJ, Bioinformatics, 32 (2016) 3532-3534.

[13] G. Cho, J. Dodds, J. Santamarina, Particle Shape Effects on Packing Density, Stiffness and Strength of Natural and Crushed Sands-Internal Report, Georgia Institute of Technology, 33pp, (2006).

[14] R.D. Hryciw, J. Zheng, K. Shetler, Particle roundness and sphericity from images of assemblies by chart estimates and computer methods, Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 142 (2016) 04016038.

[15] E.D. Sneed, R.L. Folk, Pebbles in the lower Colorado River, Texas a study in particle morphogenesis, The Journal of Geology, 66 (1958) 114-150.

[16] R. Rorato, M. Arroyo, E. Andò, A. Gens, Sphericity measures of sand grains, Engineering Geology, 254 (2019) 43-53.

[17] G.-C. Cho, J. Dodds, J.C. Santamarina, Particle shape effects on packing density, stiffness, and strength: natural and crushed sands, Journal of geotechnical and geoenvironmental engineering, 132 (2006) 591-602.

[18] J. Fonseca, C. O’Sullivan, M.R. Coop, P. Lee, Quantifying the evolution of soil fabric during shearing using directional parameters, Géotechnique, 63 (2013) 487-499.

[19] R. Askari, S.H. Hejazi, M. Sahimi, Effect of deformation on the thermal conductivity of granular porous media with rough grain surface, Geophysical Research Letters, 44 (2017) 8285-8293.

[20] W. Dai, D. Hanaor, Y. Gan, The effects of packing structure on the effective thermal conductivity of granular media: A grain scale investigation, International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 142 (2019) 266-279.

[21] G. Cheng, A. Yu, P. Zulli, Evaluation of effective thermal conductivity from the structure of a packed bed, Chemical Engineering Science, 54 (1999) 4199-4209.

[22] V. Smailovic, V. Podobnik, I. Lovrek, A methodology for evaluating algorithms that calculate social influence in complex social networks, Complexity, 2018 (2018).

[23] G. Fu, S. Wilkinson, R.J. Dawson, A spatial network model for civil infrastructure system development, Computer‐Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, 31 (2016) 661-680.

[24] A. Tordesillas, Q. Lin, J. Zhang, R. Behringer, J. Shi, Structural stability and jamming of self-organized cluster conformations in dense granular materials, Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 59 (2011) 265-296.

[25] J.H. van der Linden, G.A. Narsilio, A. Tordesillas, Machine learning framework for analysis of transport through complex networks in porous, granular media: a focus on permeability, Physical Review E, 94 (2016) 022904.

[26] A. Tordesillas, D.M. Walker, Q. Lin, Force cycles and force chains, Physical Review E, 81 (2010) 011302.

[27] R.K. Desu, A.R. Peeketi, R.K. Annabattula, Artificial neural network-based prediction of effective thermal conductivity of a granular bed in a gaseous environment, Computational Particle Mechanics, 6 (2019) 503-514.

[28] L. Papadopoulos, M.A. Porter, K.E. Daniels, D.S. Bassett, Network analysis of particles and grains, Journal of Complex Networks, 6 (2018) 485-565.

[29] S. Ju, J. Shiomi, Materials Informatics for Heat Transfer: Recent Progresses and Perspectives, Nanoscale and Microscale Thermophysical Engineering, 23 (2019) 157-172.

[30] H. Wei, S. Zhao, Q. Rong, H. Bao, Predicting the effective thermal conductivities of composite materials and porous media by machine learning methods, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 127 (2018) 908-916.

[31] E.J. Kautz, A.R. Hagen, J.M. Johns, D.E. Burkes, A machine learning approach to thermal conductivity modeling: A case study on irradiated uranium-molybdenum nuclear fuels, Computational Materials Science, 161 (2019) 107-118.